Mergers Predicated on Scale Often Fail to Yield Promised Efficiencies

There are many measures that summarize banking performance, but in terms

of the immediate effectiveness of a financial institution, one of the most

insightful measures is the efficiency ratio. Whereas measures such as return on equity remain dependent on the

bank’s capital structure at the time and return on assets gives no insight into

the scale of expenditures required to generate those returns, the efficiency

ratio neatly captures both sides of the income equation. There are only two primary ways to increase earnings in the

banking industry: sell more or spend less. The efficiency ratio captures

success at both tactics, and is therefore an important measurement for

institutions to consider when evaluating future growth strategies – including

organic expansion or a prospective merger.

There are many measures that summarize banking performance, but in terms

of the immediate effectiveness of a financial institution, one of the most

insightful measures is the efficiency ratio. Whereas measures such as return on equity remain dependent on the

bank’s capital structure at the time and return on assets gives no insight into

the scale of expenditures required to generate those returns, the efficiency

ratio neatly captures both sides of the income equation. There are only two primary ways to increase earnings in the

banking industry: sell more or spend less. The efficiency ratio captures

success at both tactics, and is therefore an important measurement for

institutions to consider when evaluating future growth strategies – including

organic expansion or a prospective merger.

Bankers have often justified mergers in the name of efficiency, and theoretically, that makes sense. In fact, on most earnings calls in which two banks are announcing a merger, the reasoning provided is the expectation of tremendous efficiencies. However, the reality often diverges from this assumption and at best, efficiency is a step function rather than a function of continuous improvement. As a result, many financial institutions fail to generate the efficiencies on which the mergers were predicated.

Effective Measurement Tool: Efficiency Ratio

A bank's efficiency ratio is a statistic used to gauge how effectively a bank spends its money as it grows, and is often used by analysts to evaluate a bank's performance against peer institutions. It is calculated by dividing a bank's non-interest expenses by its total revenues, net of funding costs. In other words, it illustrates how many cents in expense it takes to generate each dollar in revenue.

Mergers Predicated on Efficiency Gains

So why are larger banks, especially those formed via larger-scale mergers, not showing markedly superior efficiency ratios than smaller banks? There are a multitude of reasons why mergers are not generating promised efficiencies, including that some merger gains take a longer period to realize. Costs can be difficult to shed, or offset by one-time expenses; for example, severance payments to terminate top executives, write-downs on the disposition of shuttered branches, or penalties for early cancellation of vendor contracts. Additionally, entering a larger asset tier can bring additional regulatory expenses, as banks in certain asset tiers are subject to greater oversight; and can also bring constrained revenues. Anytime institutions are predicating mergers of scale for improving financial performance, it is important to recognize there is also a tradeoff between cost over cost savings, especially when back-office operations and technology integrations significantly increase in complexity.

However, there is evidence of sweet spots, or

bands of asset size where banks and credit unions can reach only a certain

efficiency ratio threshold, but will then see notable improvements from a leap

into a different asset tier.

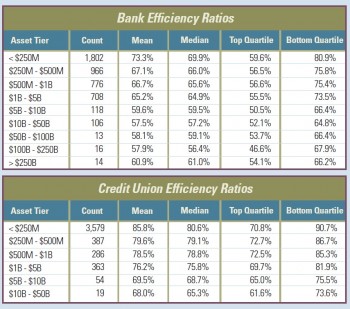

Across the industry, banks with assets of less than $250M demonstrate a median efficiency ratio of 70%; in other words, it typically takes banks in that tier 70 cents of noninterest expense to create one dollar of net revenue. For this size institution, scaling to the next asset tier (defined at $250M to $500M), can yield immediate gains, with the median ratio in that tier falling to 66%; i.e., it now takes four cents less to generate each dollar of revenue.

However, the efficiency ratio then appears to plateau, with no notable improvements in the median efficiency ratios of banks in the $500M to $1B asset tier or the $1B to $5B tier. Rather, marked efficiency gains are not realized until banks reach the $5B to $10B tier; where the median efficiency ratio falls to 60%. Thus, merging to a size below $5B may make sense only if executed as a predicate to subsequent growth into that $5B+ asset tier. And merging beyond the $10B tier appears to demand an honest assessment of possible efficiency gains before execution.

Similarly, credit unions demonstrate minimal difference in efficiency ratios between institutions with less than $250M in assets, versus those with $250M to $500M or $500M to $1B in assets. Credit unions see modest gains by growing into the $1B to $5B asset tier and more significant gains moving into the $5B to $10B asset tier.

In conclusion, merging for scale is not a guaranteed strategy to improve efficiencies. Institutions should plan merger and organic-growth strategies with the above thresholds in mind.

About the author:

Steve Reider is the co-founder and president of Bancography, a financial services consulting firm. Bancography is a financial services consulting firm that offers Bancography Plan, a branch planning software tool, as well as custom branch network optimization and primary marketing research services. Bancography Plan allows financial institutions to evaluate potential merger candidates, recommending which branches to keep or close and the corresponding financial implications for those decisions.